Is an Airbnb in Medellín better business than a hotel?... Just like smuggling is "better business" than complying with the law.

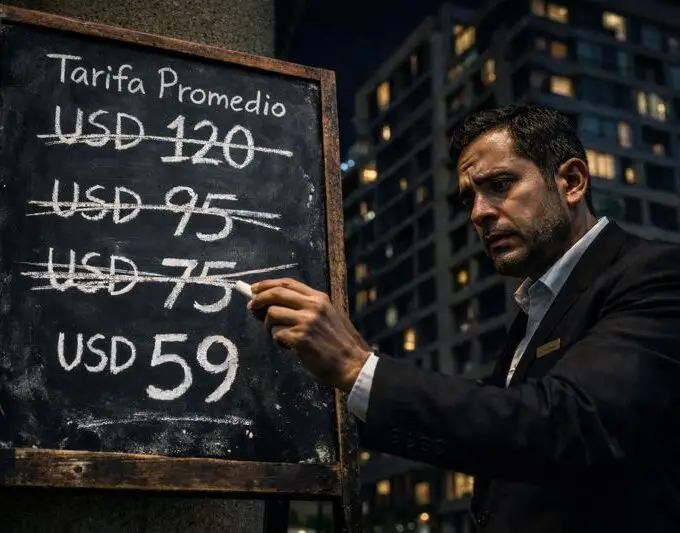

You probably saw the news in El Colombiano that Medellín has just entered the global top of cities with the most properties listed on Airbnb. With 4.07 properties per thousand inhabitants, it is on par with Madrid and Stockholm. A figure that seems to be a source of pride... until you ask yourself: how did it get there?

The answer is simple, albeit uncomfortable: operating informally is not only easy, it is profitable. And more and more people are realizing this. There is no need to guess here. You just have to look at how things work to understand why, when it comes to making money, being informal is a better strategy than complying with all the rules.

I write this list with a touch of irony, since my mother used to tell me when I was little: “Laugh so they don't see you crying.” Because when illegality becomes a business model and you work in hospitality, one of the most regulated industries in the country, seeing the advantages enjoyed by illegal Airbnb operators makes you want to cry so much that you prefer to laugh.

1. Buy low, rent high: Low blend for commercial purposes

While hotels must be built on high-density land—which is more expensive and regulated—many informal Airbnb operators set up their businesses in residential areas, where they know full well that it is not allowed. But they do it anyway. The land costs less, they don't need tourist construction licenses, and, in general, no one gives them any trouble unless a neighbor complains.

The trap starts with the price of the property. In mixed-use areas, where hotel activity is permitted, the square meter can cost between 30% and 60% more than in residential areas. That translates into higher acquisition, rental, design, and technical requirements costs. A legal hotel starts at a disadvantage. The informal operator, on the other hand, plays by different rules from the outset, even though they know they shouldn't. The irony is that these same people often express outrage at corrupt politicians, without realizing that they are doing the same thing: taking advantage of the system knowing that it is wrong.

Result: low costs, high revenues, and zero leveling in competition.

2. Invoice? VAT? What's that?

Most informal Airbnb hosts do not issue invoices, do not charge VAT, and are not even registered as businesses. They operate in a fiscal gray area, where margins grow and obligations disappear. For them, declaring income is optional. For a hotel, it is the law.

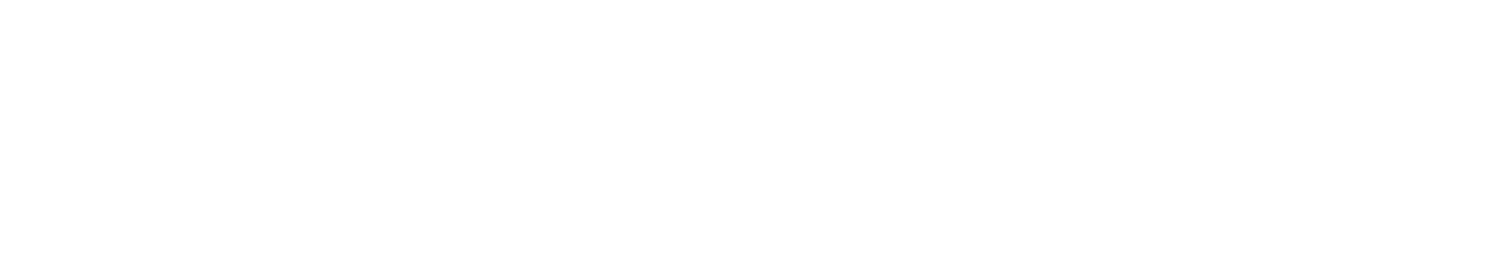

This difference creates a structural gap that undermines any notion of fair competition. The hotel pays VAT on each night sold, which represents an additional 19% that increases its final rate for nationals. Meanwhile, the informal host can charge less and still earn more, simply because they do not bear the tax burden. It is the fiscal equivalent of a race where one of the runners has to carry a backpack full of stones while the other runs free, light, and unsupervised.

And what's worse: everyone knows this is how it's done. Many even recommend it. It's such a normalized informality that it seems like an accepted strategy. As if tax evasion were a natural part of business, when in reality it's one of its biggest pitfalls.

3. Airbnb does not review RNTs

The National Tourism Registry is required by law. But Airbnb does not connect to the official database. All you have to do is enter any number—real or made up—and the platform accepts it without verification or validation. As a result, many operate without registration and without anyone monitoring them.

This is not a technical error. It is a structural flaw. A system that requires registration but allows anything to be declared without confirmation is designed to fail. Meanwhile, those who do comply with the procedure must renew every year, pay for the renewal of their business registration, and face penalties if they do not do so on time.

This completes the perfect cycle: operating without rules is not only possible, but profitable. If the platform does not validate, if the state does not monitor, and if the market does not punish, then the message is clear: being informal works. Legality is for the naive (hotels). And in the meantime, those who comply pay for everyone. Literally.

4. FONTUR, that's for hotels... or is it?

So far, we have cheap real estate, without RNT (rental income tax) and without VAT. With that, the next step is easy: don't pay taxes or contributions. Hotels and other formal tourist accommodations must contribute to FONTUR, a fund that finances the promotion of tourism in Colombia. It is a kind of mandatory payment to the system of which we are a part. But if AIRBNB has no registered company, no invoices, and no RNT, it is not going to start paying taxes just because.

Informal Airbnbs are set up on a system financed by others. They receive tourists, benefit from national and international marketing, use the city's infrastructure... and contribute nothing. Once again: the smart live off the dumb.

5. Silver up, income down

In addition to everything we have seen, and as if that were not enough, many Airbnb hosts set up their accounts so that the income generated goes directly to bank accounts in the United States, Central America, or Europe. This way, they not only avoid declaring income in Colombia, but also dilute the financial trail. “All legal”... for them. Invisible to the DIAN, invisible to any local entity that wants to audit.

And while we hoteliers must declare income, pay withholdings, file monthly reports, and prepare annual tax returns, informal Airbnb operators live happily in the shadows. They receive payments in dollars, spend in pesos, and leave no trace. To top it off, if they are ever asked why they don't file taxes, they can simply say, “That account is in the name of a relative in Miami.”.

This type of maneuver, which in other sectors would be seen as evasion, is the biggest “strategy” here. And the worst thing is that it is done with complete normality, without fear of anything. The system “allows it,” the platform “facilitates it,” the city “ignores it,” and the AIRBNB operator “enjoys it.”.

6. Receptionist? Better to have a digital name tag.

Reducing costs is the rule. No staff, no protocols, no supervision. Just a digital key sent via WhatsApp. Zero fixed costs, zero responsibilities. But also, zero control.

The same technology that allows people to operate from their cell phones is what makes it easy for anyone to enter, without verification, without registration, without consequences. Who comes in? Who goes out? What do they do inside? No one knows and no one answers. In a hotel, every guest must register, show identification, be entered into a database that is connected to the tourist police, and in many cases, pass through security cameras. In an informal Airbnb, in most cases, an access code is sufficient.

This model opens the door—literally—to theft, microtrafficking, sexual exploitation, use of minors, and other risks that can lead to asset forfeiture or criminal proceedings. But the goal of these Airbnb operators seems to be: anything goes, as long as it brings in more money at the end of the month. Because as long as it works, as long as the apartment isn't damaged and no one reports it, it continues to be rented out. That's how it works. That's how you make money. And we give ourselves a pat on the back and move on.

7. All income, zero expenses

Many believe they are earning millions because they do not calculate actual costs: administration, services, laundry, maintenance, local taxes, financial expenses... The return seems high because they often do not do their accounts correctly. Or worse: because the person operating the Airbnb only reports what they want to the owner.

In this informal model, without invoices or standardized reports, there is ample room to fudge the figures. And without an accounting system, without income records, without external control, whatever the Airbnb operator says goes. This illusion of profitability is fueled by a cash culture, not an accounting culture. As long as money is coming in, it feels like you're making a profit. But when you add up all the operating costs, hidden expenses, and contingencies—such as damage, claims, or vacancies—the picture changes. What may seem like a gold mine sometimes turns out to be income that barely covers costs, or worse, operates at a loss without the owner realizing it.

8. If there is no record, it did not happen.

When a third party entrusts their property to an informal Airbnb operator, everything is based on trust. In many cases, there is no traceability, no auditing, and no reports that can be cross-referenced with external data. And since income is not reported, it is easy to inflate costs, reduce apparent profits, or even invent damages to justify deductions. The owner often has no way to verify anything.

It is even riskier when the owner is an elderly person or someone without digital knowledge, who does not know how to access their Airbnb account or even whether their property is listed under another name. In such cases, whatever the operator says becomes the only possible truth.

Without billing, without RNT, and without accounting, the relationship is based solely on what the operator decides to show. And that imbalance of information can open the door to subtle but constant abuse. There is no need to steal brazenly if you can cut corners with technique. The result is the same: maximizing revenue at all costs, mindlessly and painlessly.

9. Insurance? That's definitely not a problem...

No liability policy, no damage coverage, nothing. Most informal operators consciously decide not to take out insurance because they see it as an unnecessary expense since “Airbnb has insurance.” They often say, “That never happens.” But it does happen. And when it does—a fire, structural damage, an accident, a guest who destroys everything—the cost is borne by the owner. Out of their own pocket.

And that's when they realize that what they saved on insurance for months or years evaporates in a single incident. Replacing furniture, repairing damage, compensating neighbors, or even facing legal claims can be more expensive than all their accumulated income. But in the meantime, they continue to operate without protection. Because the model is based on praying that nothing happens, because at the end of the day it is “very profitable”... until it is no longer so.

10. The clever live off the foolish.

The system is so permissive that many informal operators end up earning more than legal hotels. They don't pay taxes, they don't comply with regulations, they don't finance the sector... and this means that practically everything is profit. Not because they are smarter, but because—just like smuggling—everything is structured to work, generate profits, and have no consequences. Those who break the rules earn more, while those who comply bear the brunt. And so, they rejoice in being part of Airbnb's global top. A record that gives more cause for reflection than celebration.

Meanwhile, those of us who comply with the rules see how informality is not only tolerated but rewarded. At the end of the day, the conclusion is as absurd as it is painful: being legal is bad business. That's why we often feel like closing our hotels, opening a bunch of low-quality Airbnbs, sending our money to the United States, and dedicating ourselves to “enjoying the good life.”.

But no. After meditating for less than five seconds on these impulses of illegality disguised as financial common sense, I prefer to do what is within my power: to put on record what many prefer to keep quiet. Because someone has to write these uncomfortable truths. Even if it's just so we don't forget that, even when competing against a business that rewards tax evasion, there are still those of us who choose to compete within the law. And yes, sometimes you have to laugh so you don't cry.

Final note

Not all hosts are illegal. There is a small group of operators who are registered, who issue invoices, who pay taxes, and who comply with all obligations. To them, I offer my respect. And also my apologies if this article makes them feel included in a criticism that does not represent them. It is not against them, although, paradoxically, they are also affected by this disorder.

Because every informal apartment that evades regulations lowers the value of those who do things right. Because competing with prices subsidized by illegality is exhausting, and because their efforts are diluted among the majority who simply decide not to comply. They are the righteous minority in a system that, sadly, rewards the opposite.

As long as informality remains the most profitable path, we will continue to fight together against the tide. Hopefully, one day the system will support us as much as it punishes us today.

Alejandro Gonzalez

Co-founder of Blackroom

Alejandro Gonzalez Uribe

Co-founder of BLACKROOM and MACCA. I'm obsessed with turning good ideas into profitable hotels—built from the user's desire and the investor's logic

Recent Posts

Related Articles

The mistake no one wants to admit: Medellin builds more hotels than it can fill

What “El Colombiano” fails to see Today I read the column...

Hotel oversupply in Medellín. More tourists does not mean more reservations.

Let's make one thing clear: Medellín is not empty. Nor did it cease to be...

3,000 new hotel rooms are coming to Medellín. Too much supply?

Tourism growth is not enough when supply grows unchecked During...

Rate war: This happens when Medellín becomes flooded with hotels and Airbnbs without any control.

Medellín continues to grow, but the market has changed. Hotels...